Title | The Capacity of a Line

Proposal by | Christopher Prinsen

Advisor | Perry Kulper

Advisor | Perry Kulper

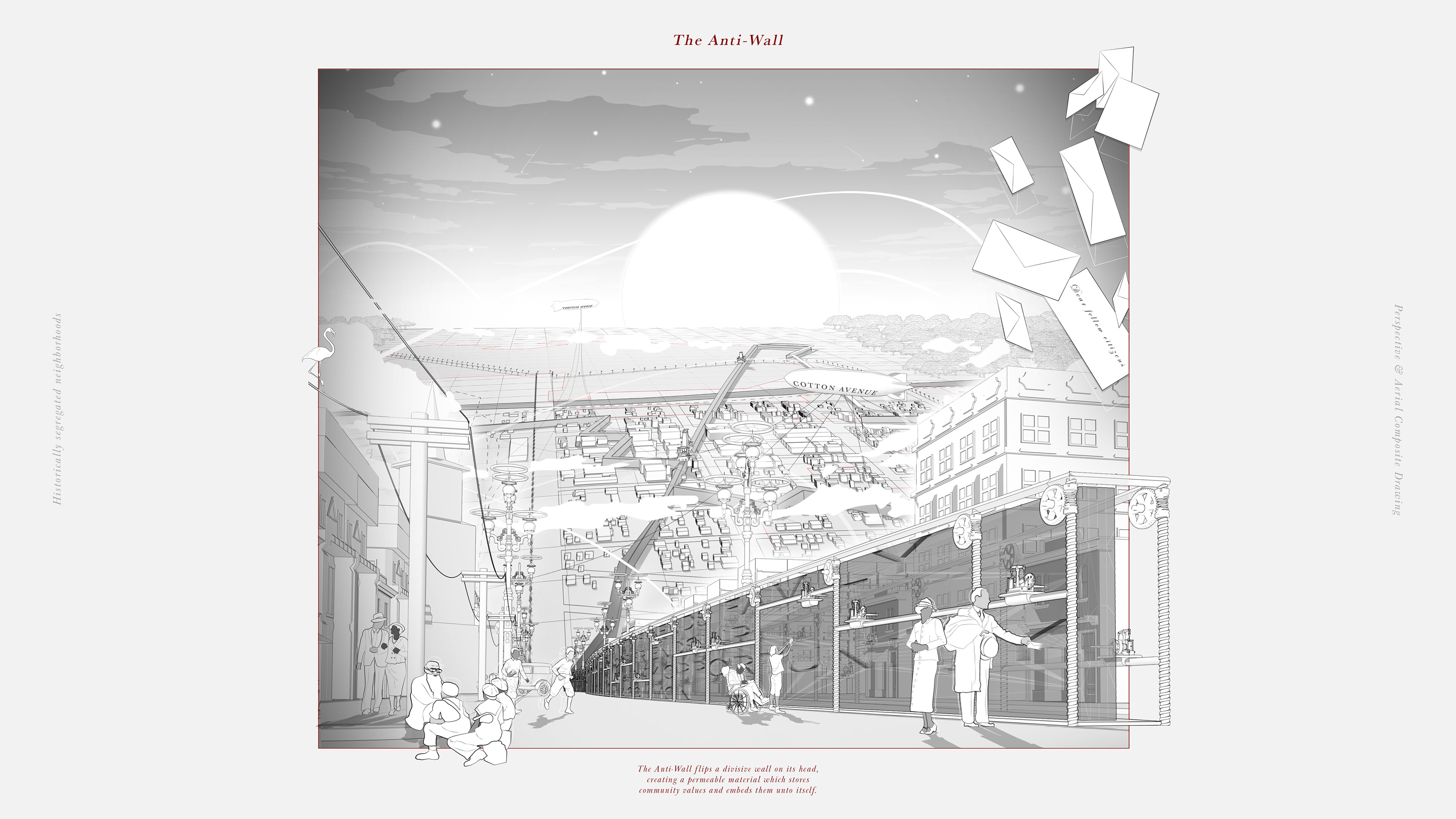

On the one hand a line is a divisive tool that tears people apart, yet on the other hand, a line is a powerful advocate of unity, inclusivity, equality, and rectitude. A single line on a map has divided nations, propagated inequity, and deleted Africa’s geographical landscape. A line with altruistic legibility has mapped ancient treasures, generated beautiful imaginary universes, and even bridged historically segregated communities.

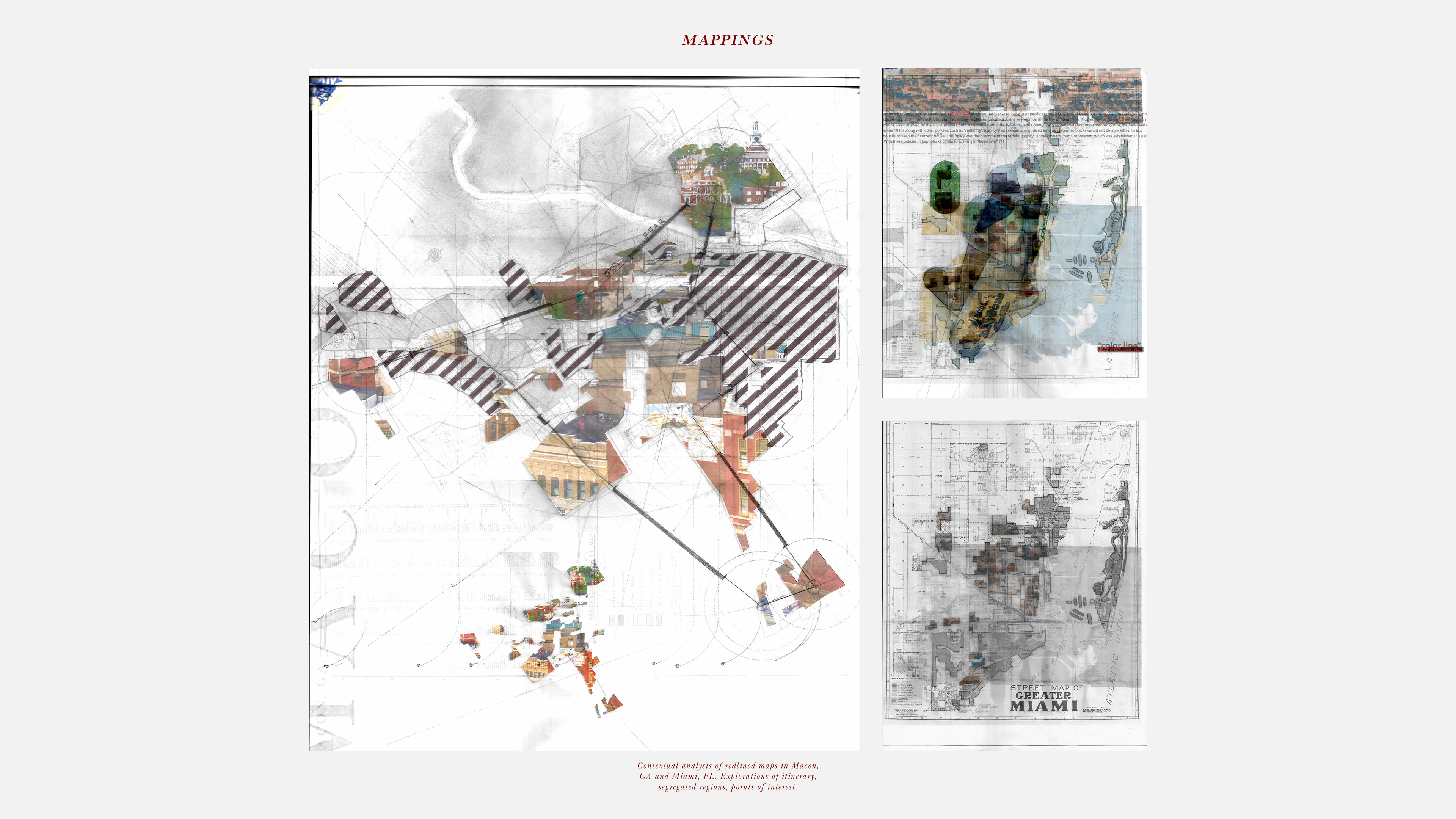

In 1938 the Homeowners Loan Corporation drew a line around Macon, Georgia on a map, colored it red, and gave it a D, the worst classification possible. The line denoted a hazardous place to underwrite mortgages and was based on the false belief that Black residents would undermine property values. Regrettably, the line forever codified patterns of racial segregation and disparities in access to housing, credit, and wealth accumulation.

Lines just like this were carved into all major cities in the United States. As recent as 2010, studies were found that differences in the level of racial segregation, homeownership rates, home values, and credit scores are still apparent where these boundaries were drawn. Throughout the past 90+ years, these maps became self-fulfilling prophecies and further fueled white flight and rising racial segregation. The classifications were later used by the Veterans Administration, as well as the Federal Housing Administration to determine who was worthy of home loans post WW2, when homeownership was increasing exponentially.

The inability for these communities to obtain credit for repairs, maintenance, and even healthcare led to further deterioration of their properties. Because these lines are invisible from the ground people place the blame for the community’s disrepair on residents who do not value their homes.

Redlining was how structural racism was woven into our everyday urban fabric. It lifted the segregation away from the visible ground structures in the early 1900’s into the hidden aerial view of our present day-built environment.

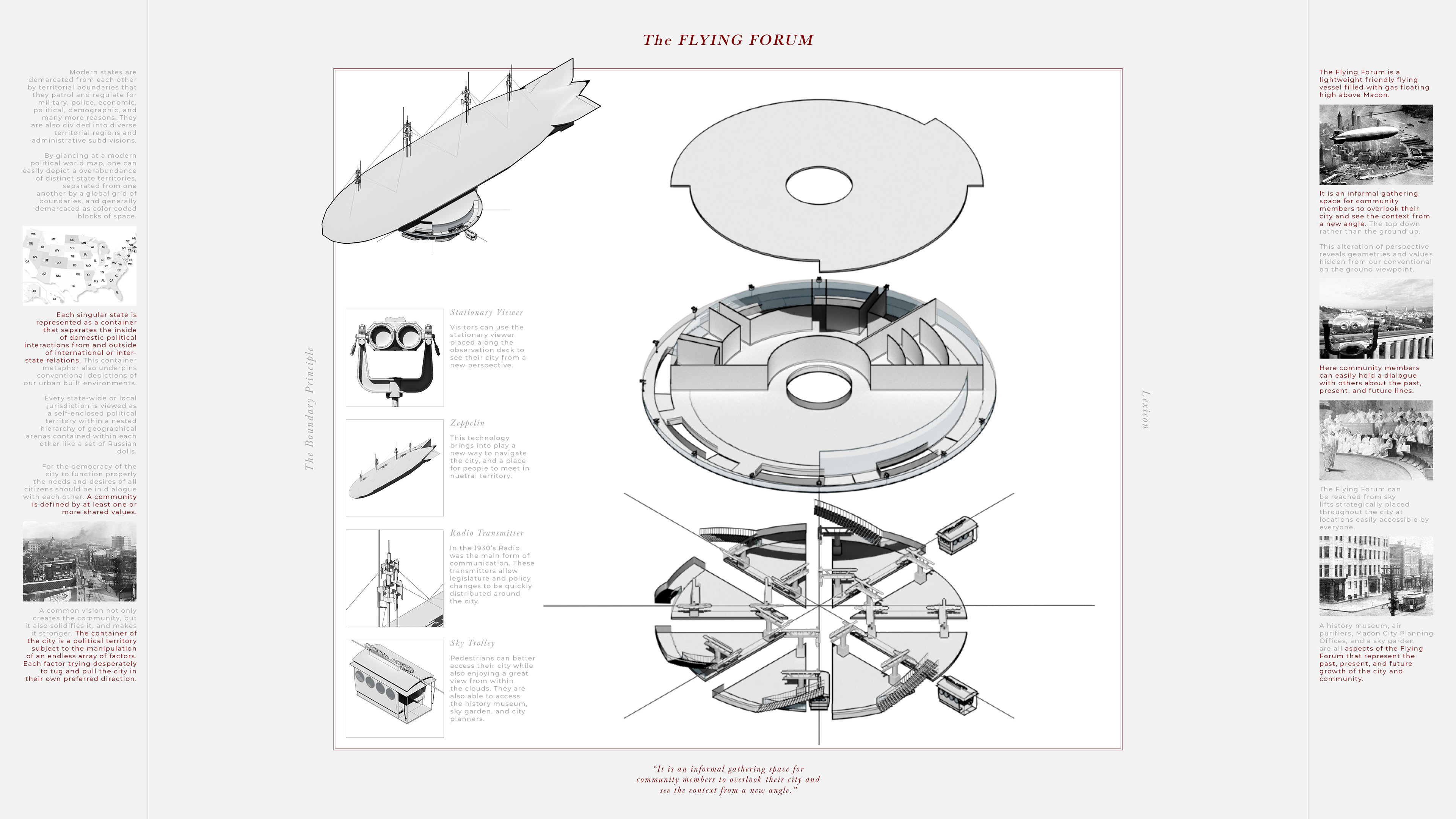

The racist policies, although now removed, have had an extremely long-lasting effect because structures can last an extremely long time. These demarcations on a map alone did not single-handedly create the segregated cities we live in today, although they played a pivotal role. As these lines start to come into focus, we are better equipped to redesign the line in efforts to cultivate a more inclusive and prosperous built environment for everyone.

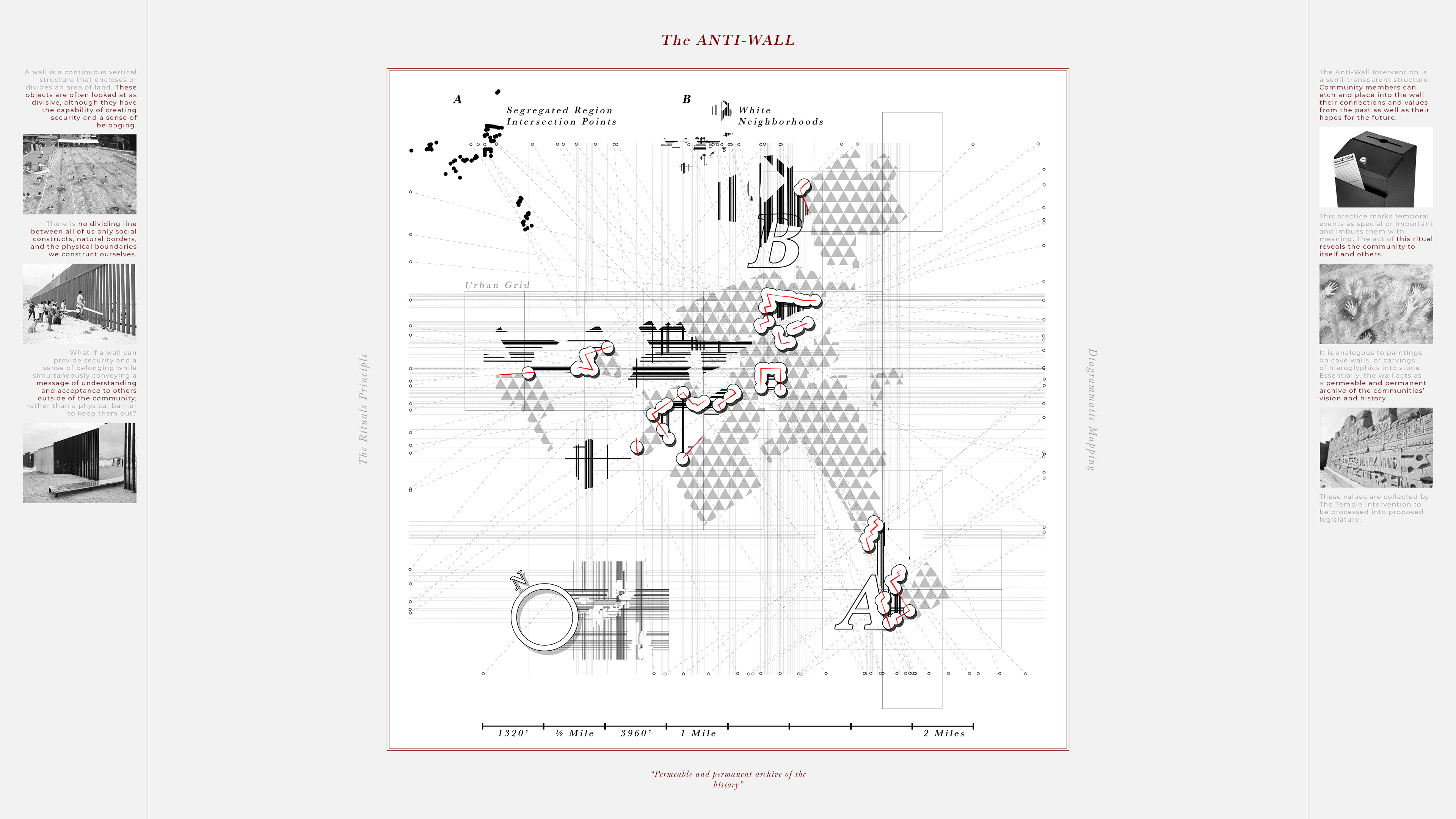

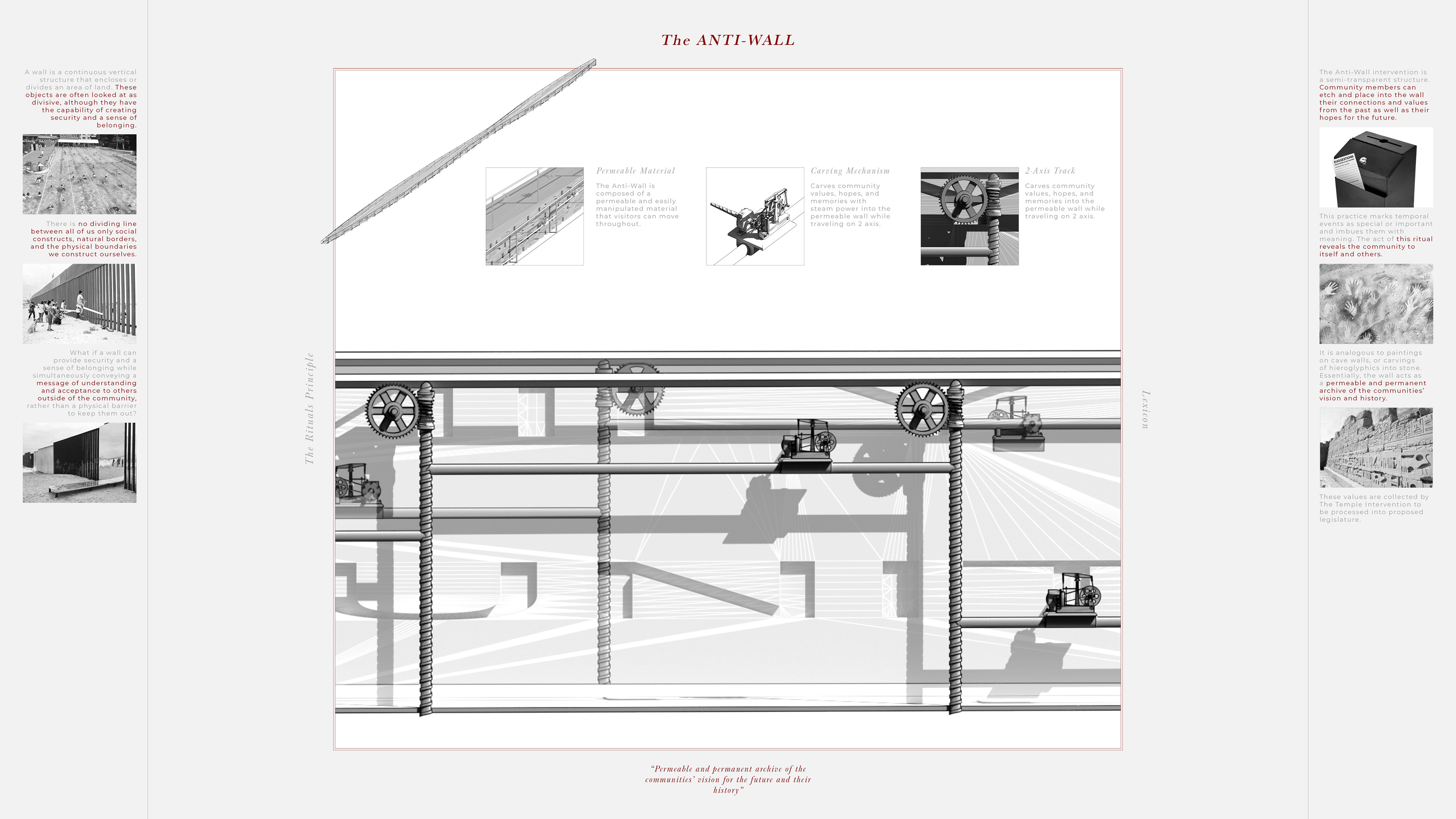

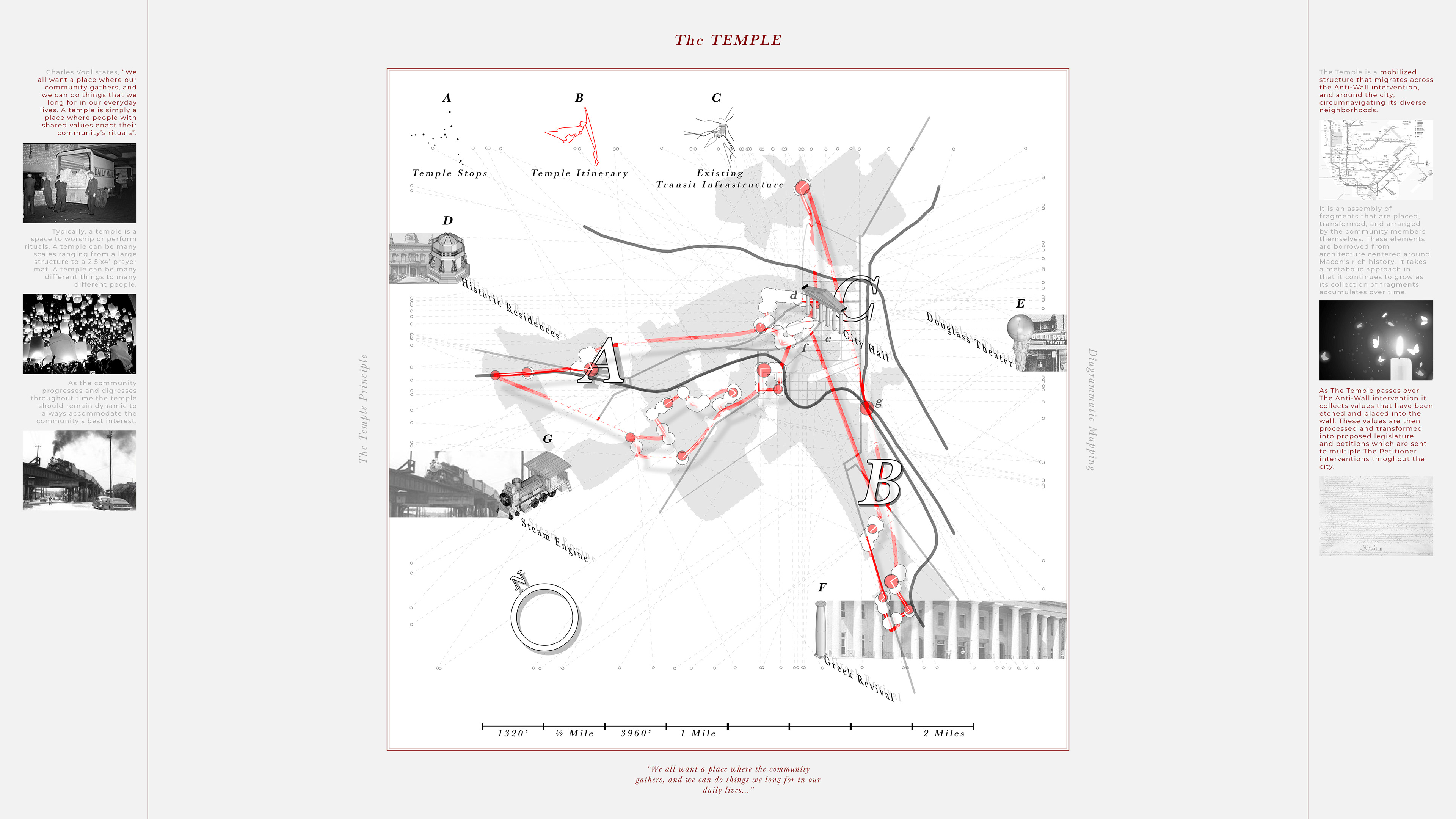

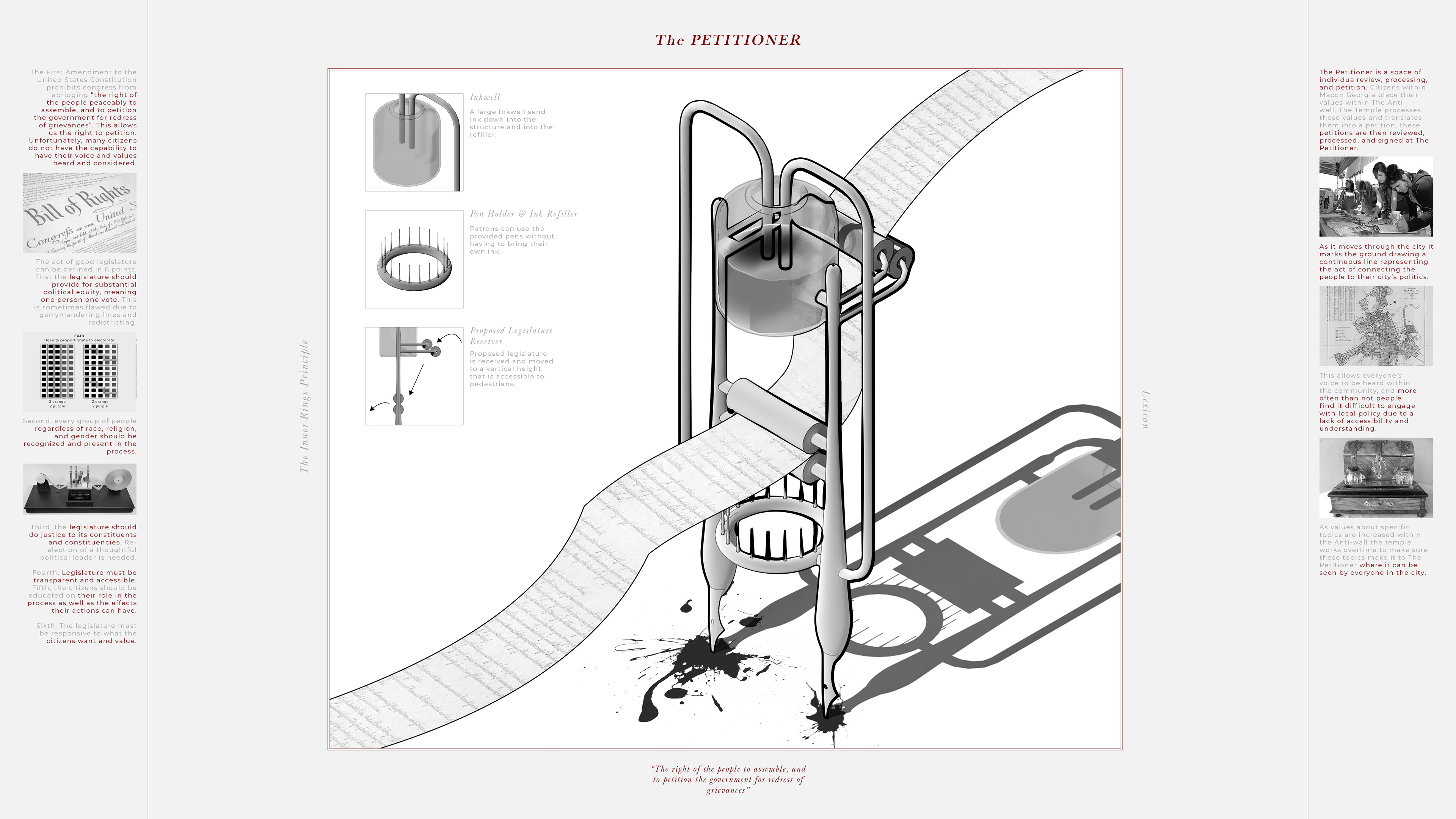

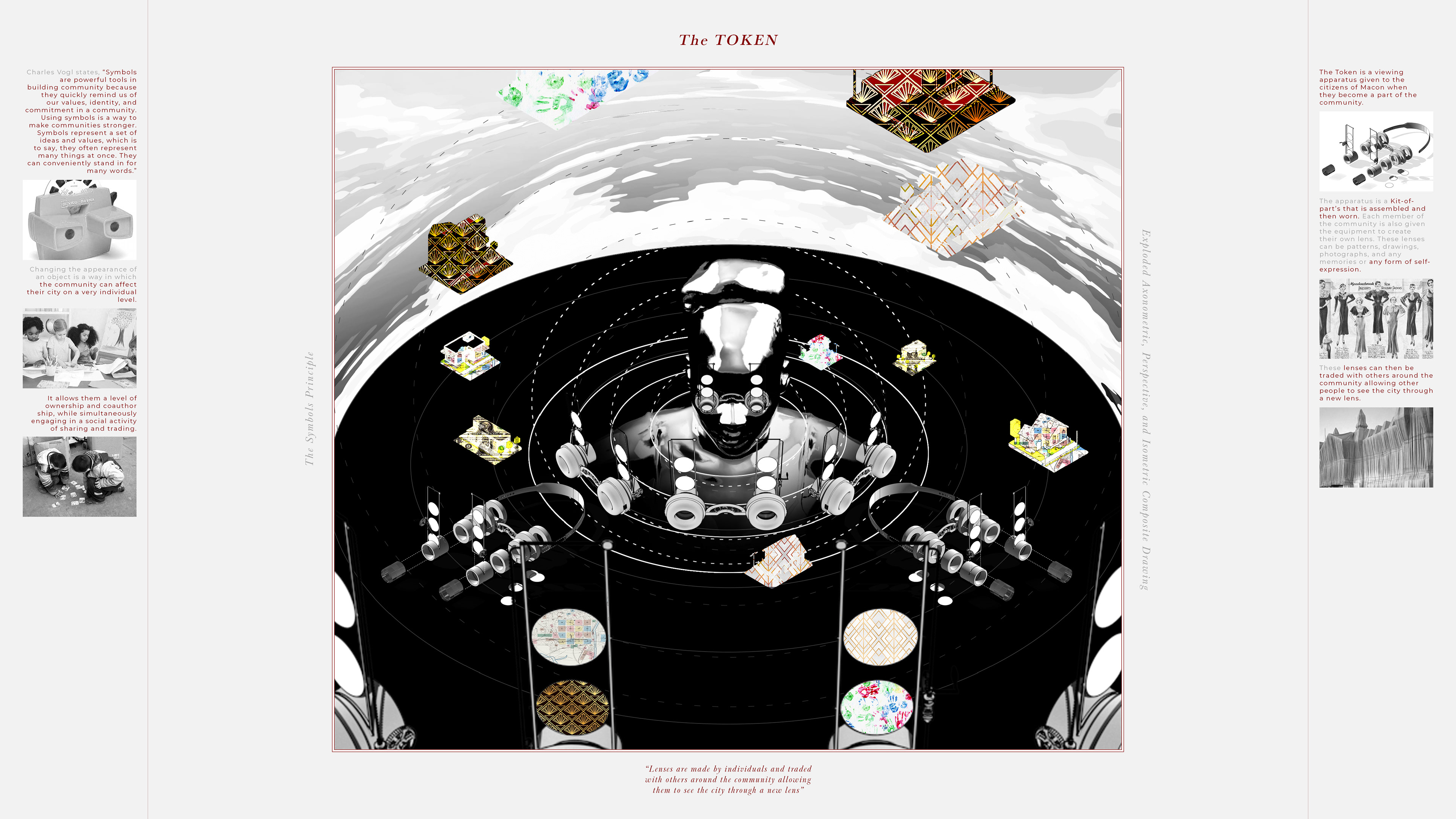

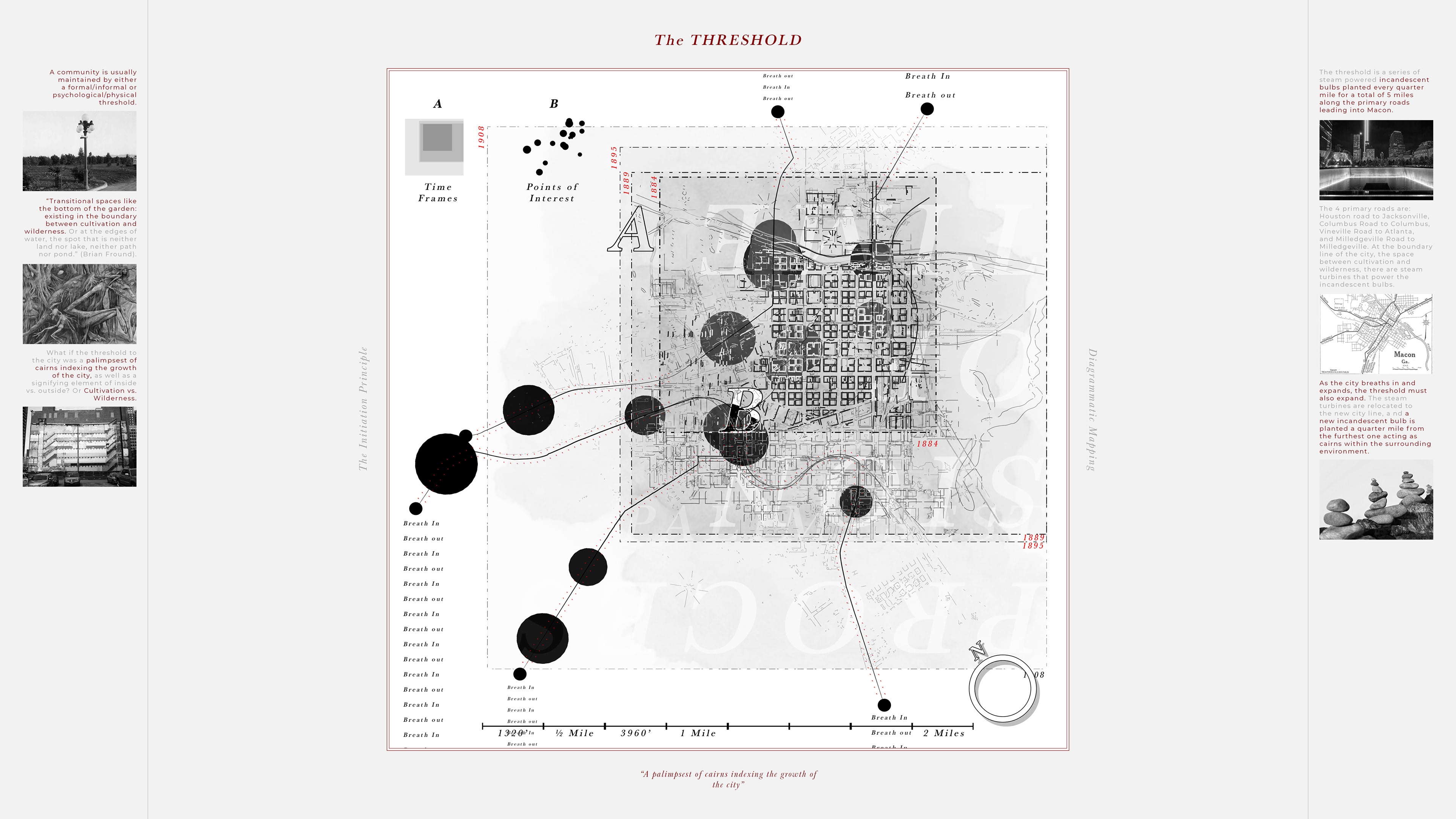

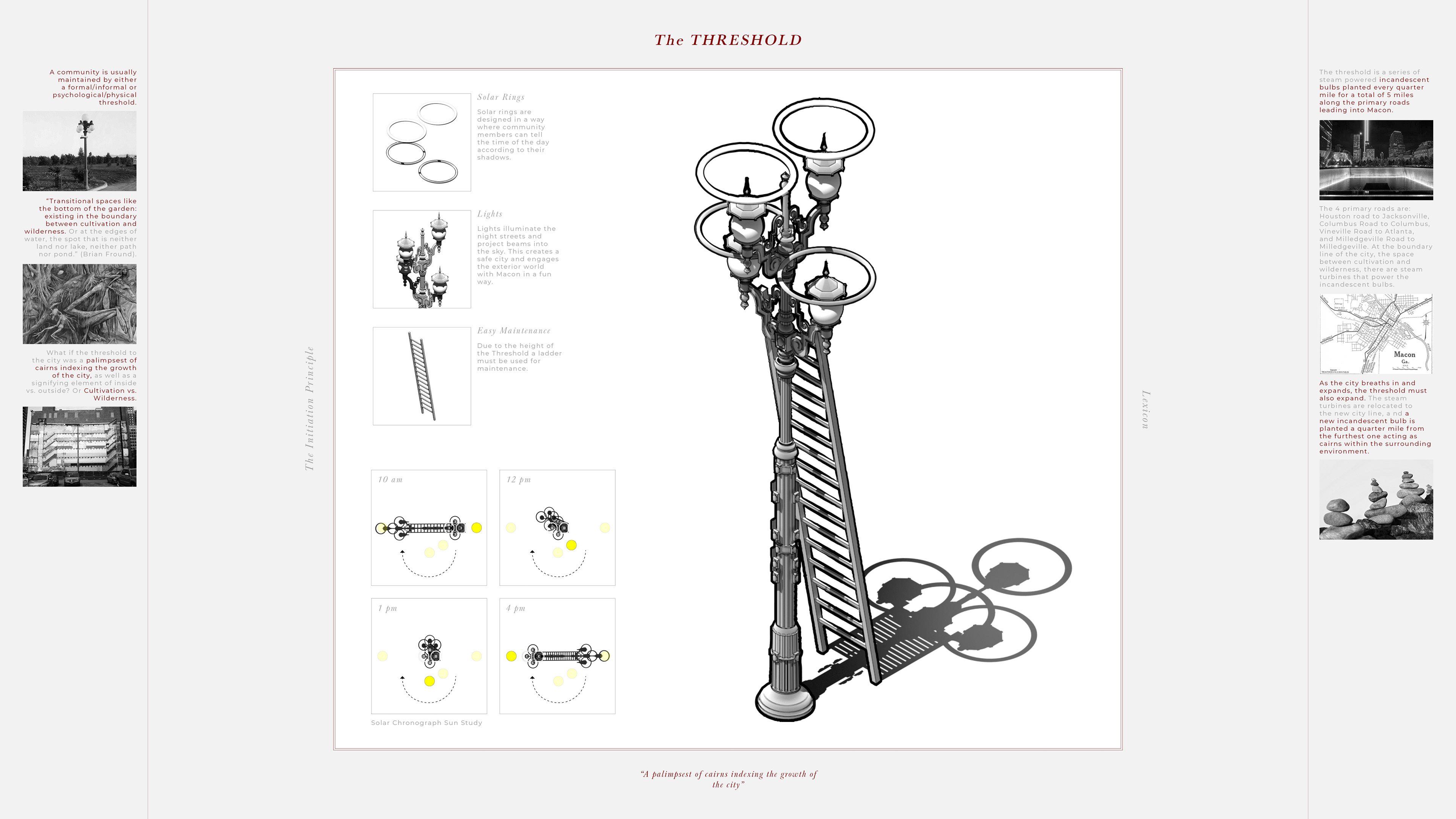

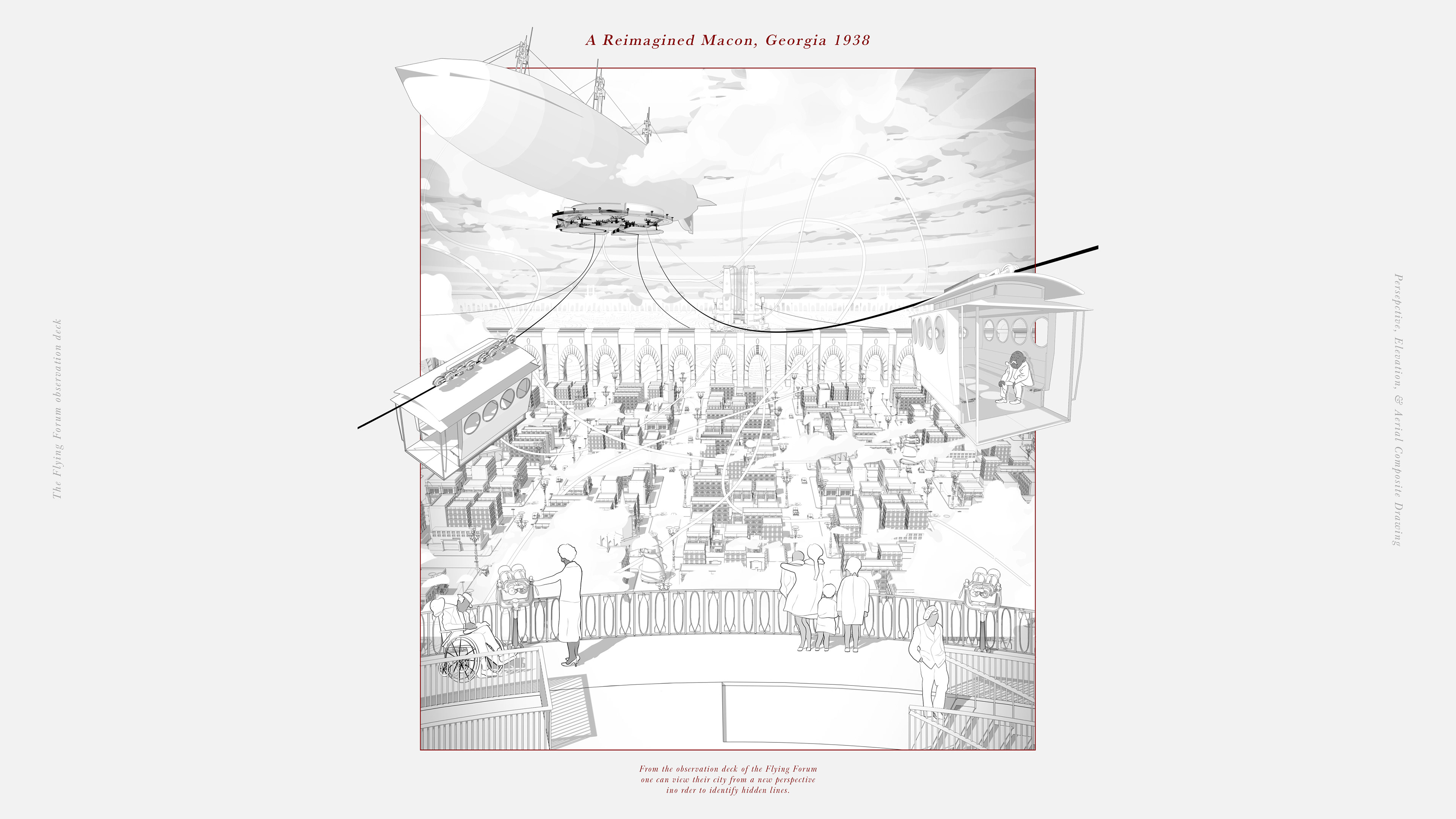

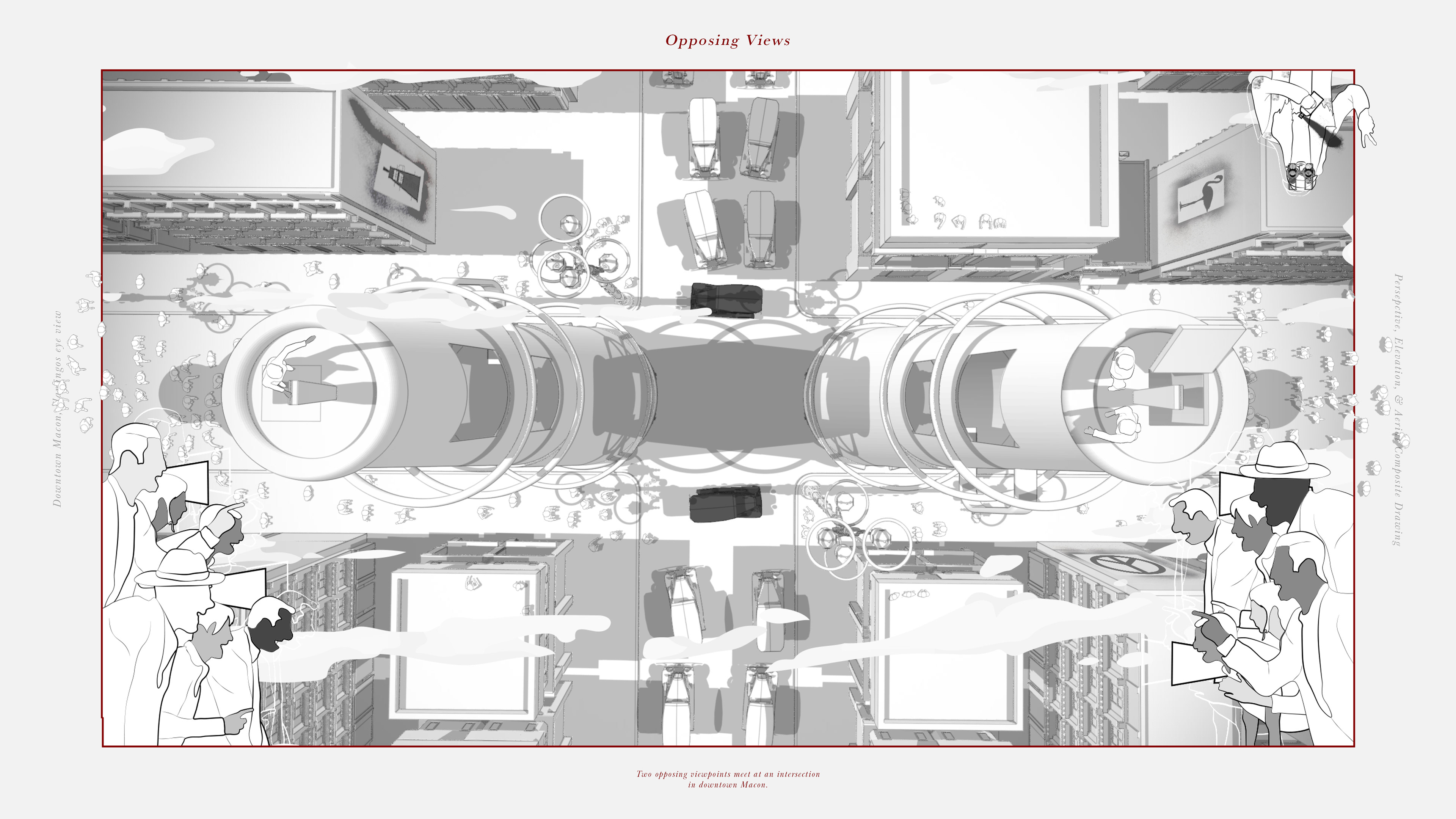

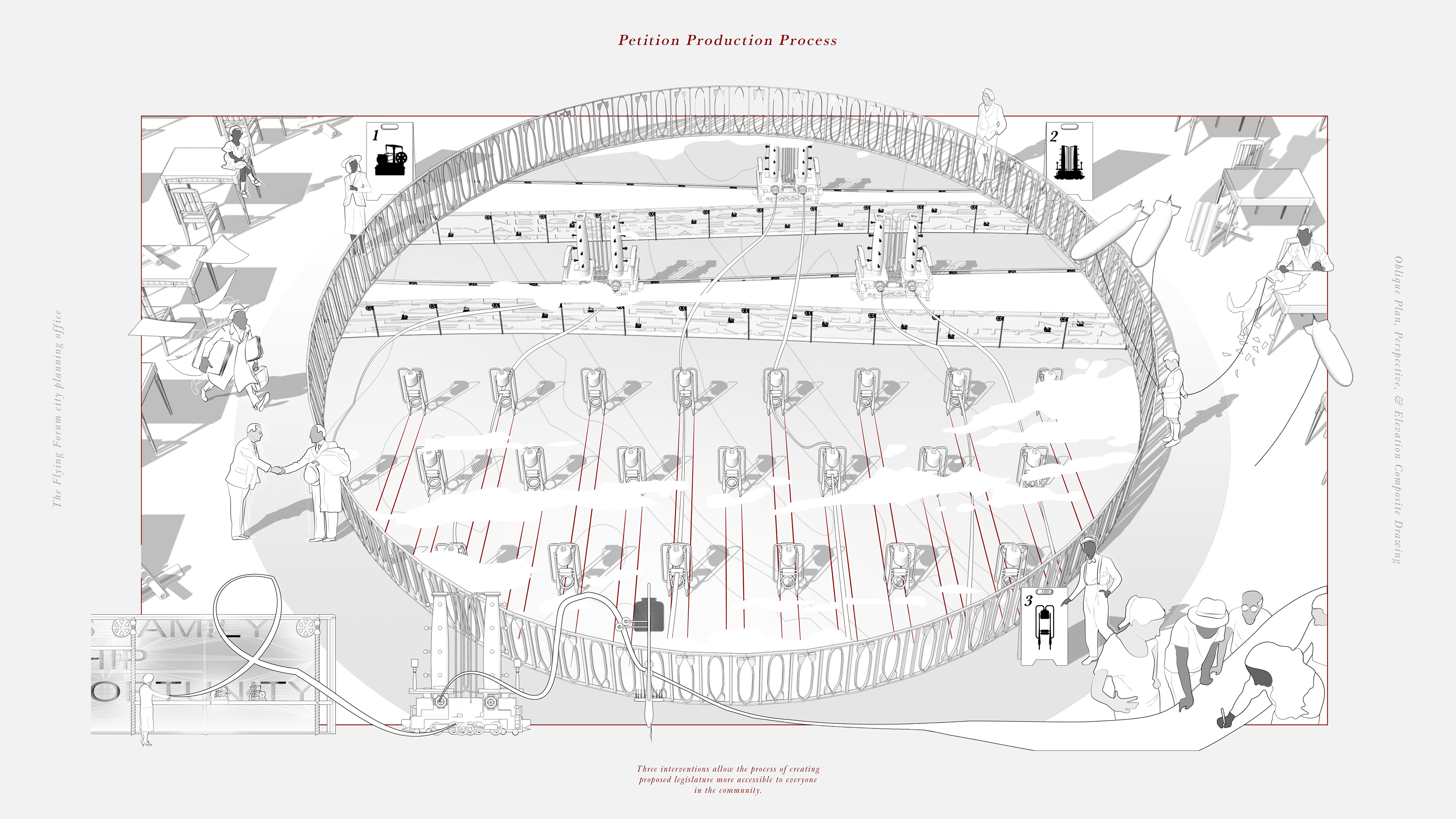

This thesis aspires to develop a series of constructed cartographic explorations and spatial interventions situated in Macon, Georgia in the year 1937. These constructs will act as a test bed on which to form a probative analysis and spatial response on the moral integrity and agency of Designers, Architects, Planners, Policy Makers, and all other “Cartographers”.

By way of interrogating a lines capacity to manipulate and create the world around us, one can derive deep holistic principles empowering us to identify and draw lines from commonalities and regions that deliberately foster unity, inclusivity, equality, and rectitude.

This thesis aspires to develop a series of constructed cartographic explorations and spatial interventions situated in Macon, Georgia in the year 1937. These constructs will act as a test bed on which to form a probative analysis and spatial response on the moral integrity and agency of Designers, Architects, Planners, Policy Makers, and all other “Cartographers”.

By way of interrogating a lines capacity to manipulate and create the world around us, one can derive deep holistic principles empowering us to identify and draw lines from commonalities and regions that deliberately foster unity, inclusivity, equality, and rectitude.